|

| Manistee River Trail Bluff |

“Sometimes you just have to walk,” Astrid said. She was talking to her brother on his front porch as his sweet little girls raced by in their plastic cars. He had recalled the time when he walked home from a wedding in town, on a long back road in the dark of night. A deer in the woods nearby had snuffled and grunted at him, a strange thing to hear, especially in the dark, at night on a lonely mountain road.

That was when the idea of backpacking–somewhere, anywhere–became so loud a buzz in her head, that she had to take action. To be outside and just walk–not around the gravel track near her home, or on the hard cement neighborhood sidewalks to the store or post office, but in a forest, for a long time, all day: that was what she was going to do. But when? Where? With whom?

The rest of that summer was used up in a road trip to see her sister in Maine and in preparation for the school year. Through September she researched where she could go, then started to plan her “walk” in earnest. She chose the Manistee River Trail Loop, in northwest Michigan.

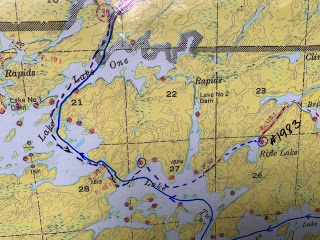

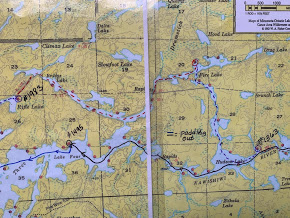

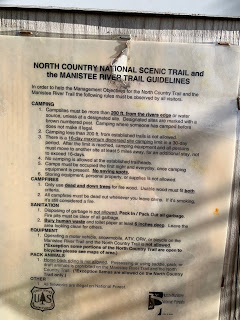

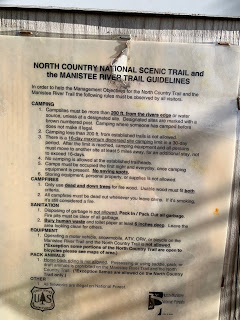

The Manistee River Trail (MRT) Loop is a 22-ish mile hike in the Manistee National Forest which, combined with a portion of the North Country Trail (NCT) (the whole of which transverses parts of MA, NY, PA, OH, MI (lower and upper), WI, MN, and ND) forms a loop connected by a suspension bridge on the north side and Red River Bridge on the south side.

“I am planning to hike–backpack–the Mannistee River Trail Loop, would you come with me?” she asked Bjorn.

He looked at her the same way he did when she asked if he would take ballroom dancing classes with her. She wanted to learn how to waltz.

She asked Snorri, even gave him a choice, “Go on a scout outing or go backpacking with me.” He chose the scout outing, which didn’t disappoint her too much.

It wasn’t really possible to learn how to ballroom waltz solo, but she could backpack solo, couldn’t she?

As she composed lists of items to bring, accumulated backpacking gear, pored over maps, reviewed others’ experiences and advice on hiking the loop, her courage waxed and waned. At night, when darkness blotted out the windows and the cold fall wind whistled, her courage faltered a little, dark thoughts filled her projected plans.

“How am I going to spend the night alone in a tiny tent in the wilderness? Alone, in the dark and maybe wind … and maybe critters?”

Eventually she leaned into the fear, accepted that she would be a little scared, but in reality she would probably be okay.

The date was based on weather first, leaf color second. She planned to use a whole weekend to do it, from Friday to Sunday, if needed. She set the original date for October 4-6, but fate intervened. So Astrid put it off until Oct 25-27 and to Snorri’s minor annoyance, joined him on his outing.

|

| NCT |

After collecting all her materials, she stuffed a borrowed external-frame backpack with 30-ish pounds of magazines and water bottles and took a hike, a dry run, in a nearby state park. She walked 2.6 miles in about an hour and wasn’t too bent and bruised from it. It was one more thing to convince her that, yes, she could do it.

The next week she was busy with cutting her supplies and obsessively checking the weather in Harrietta, Michigan (a town near the loop). And it didn’t look good, but the weather for the weekend before (10/18-20) looked great, 60℉ day/40℉ at night and nary a sprinkle. But she wanted to see Snorri perform with the band at a football game that Friday.

Needing a small nudge of guidance, she reached out to Bjorn in an e-mail, asking what he thought–when should she go?

“Every movie trailer I’ve seen on the subject seems to indicate that it is a bad idea for any female to go hiking by themselves. So, I’d be worried about either option.”

Despite his invaluable advice, in the end, the warmer weather won out. She had cold weather-camped; it involved layers, more layers and a pointed and strategic fight against cold and chill. Cold was one element she didn’t want to deal with on such a new and novel experience of backpacking. So, she would do it on the warmer weekend, but she would have to do it in just two days.

She packed her bag with 35 pounds of “necessities,” including 80 ounces of water, and in the wee morning hours of October 19, she drove north toward Harrietta, Michigan.

It was a glorious fall morning, and the sky and trees along the highway rejoiced in it. It was the most pleasant drive she had taken in very long time. It was the same route to her son Olaf’s college, but this time she passed the usual exit and continued through empty highways flanked by bright yellowing foliage tinged with green.

When she arrived at the Red River Bridge Trailhead, the parking lot, boat launches and camping sites were full. Various parties there were breaking camp, having stayed there the night before. No empty spaces. So she parked along the road with other cars, used the vault toilet nearby, hefted on her pack, picked up her walking stick and “just walked,” following signs for “NCT.”

“At first things seemed to be going pretty well. They even thought they had struck an old path; but if you know anything about woods, you will know that one is always finding imaginary paths. They disappear after about five minutes and then you think you have found another (and hope it is not another but more of the same one) and it also disappears, and after you have been lured out of your right direction you realize that none of them were paths at all.”- Prince Caspian, C.S. Lewis, pg126

The path ran parallel to the road for a few hundred yards, then lead her, with white blazes, into a pleasant, thin woods, over a fallen tree, then promptly ended in a wet, mucky swamp, with no white blazes in sight.

Astrid scanned the trees to no avail, the blazes had disappeared. She backtracked, noticed a slightly inferred path, but it seemed to go in the wrong direction.

Astrid scanned the trees to no avail, the blazes had disappeared. She backtracked, noticed a slightly inferred path, but it seemed to go in the wrong direction. Using a map and GPS, she started off in what she thought was the correct direction, to the Upper River Trailhead Parking lot, which lead to the NCT. In her hurry, she tripped and fell, with all 35 pounds on her back. A little mud and struggle later, she decided to bushwhack her own path through loamy squishy forest soil, then through a roadside fern bed to reach the parking lot.

“If you see movable branches/small logs across a path, that means it’s not the right way for the MRT/NCT trail,” a wise hiker wrote in a post and at a Y in the path, Astrid heeded his instructions and avoided getting lost what would be the second time in the first hour of her hike. Up an incline filled with roots, she stopped once to take off an extra wool layer. It was going to be a nice day.

She walked for about three hours, then sat down to eat lunch at the top of a slope where the wind filtered through her coat, so she sat bundled, chewing on beef jerky, celery and granola bars, while a few groups of young hikers passed her.

She had passed a few lone women-hikers. which made her feel a little better. Two of them had dogs with them.

|

| NCT |

Most of the NCT was flanked on one side by a hill, the other a downward slope, the trail going up hill and down, circling ravines through a surprisingly thin forest. Astrid’s motto in hiking, after health problems reduced her top abilities, was “Slow and Steady.” She could walk for a long time without taking a break, just not very fast. Groups of young hikers passed her by, but she didn’t mind. Hiking was not a hurried pastime for her. Hiking was more “forest bathing,” and for that you couldn’t rush.

In the next hour, she passed the youths stopped for a break and continued to leap-frog various groups as they hiked and stopped, hiked and stopped.

The NCT ran parallel, but a long distance from the Manistee River. The trail crossed water only after about eight miles (hiking north from Red River Bridge) to Eddington Creek, then there was water everywhere in the form of the Manistee River. By 2 p.m. she had reached Eddington Creek at the north end of the NCT, then veered off the NCT onto MRT, still on the west side of the river and this is where things got confusing.

“Thank God for white blazes,” she muttered as she spotted the painted rectangles, assuring her that she was going the right way. But again, as she followed signs pointing to MRT, skirting the river’s edge on the floodplain, and back into the wood, still heading north, doubt and fatigue began to set in. The white blazes disappeared, but not the worn trail.

A fire ring with logs pulled up as seats served as a great spot for a longer rest and map study. She was on the MRT, but still on the west side of the river, which confused her slightly. The reality is that some portion of the MRT is on the west side of the river, the small portion that connects NCT to the “Suspension Bridge”. She broke down and turned on the GPS on her phone, and put in the trail from where she was to the bridge, and it guided her up an access road she had crossed shortly after coming off the NCT.

Day hikers and loopers were standing in the middle of the bridge as she squeezed by, the bridge swaying with the weight.

Once off the bridge, she turned south, onto the MRT proper, backtracking a half mile to double check the map because the white blazes turned into blue diamonds and there were signs prohibiting camping and fires. But about a mile south, (after leaving Consumer’s Energy, the people who own the land around the hydroelectric Hodenpyl Dam nearby), the forbidding signs disappeared and she started to notice tents and hikers. A lot of them.

Now came the dilemma; where to camp for the night? The MRT and NCT allowed dispersed camping, which means, as long as you followed the rules, you could camp anywhere, even outside designated campsites (though you couldn’t technically have a fire).

She walked on for a mile or so before she looked at her watch: 5:00 p.m. The sun was due to set around 7p.m. and she wanted to eat, set up her tent and bedding well before night fell. Everywhere she looked hikers were setting up camp.

“You gotta find a spot before 5:30 p.m.,” she gave herself a deadline. She walked on, past tents settled high on bluffs over the river, past illegal and risky camps set just feet away from the river, past tents set up in cozy little flat spots.

Continuing on down the trail, she passed a Scout troop setting up camp with all its usual hustle, bustle and noise.

“No, not this time,” she said and was determined to move at least out of earshot of the exuberant youths.

The MRT was more varied than the NCT, tracing regularly down into ravines and back out, crossing streams and straying to the very eroding edge of the bluff above the snaking river.

At one point the trail dipped down into a steep ravine with a vigorous little stream at the bottom, to a point where the water acted so much like a cataract that indeed, the spot was called “The Falls.”

|

| The Falls |

She crossed the little waterway, a little jealous of the group who had snagged the designated campsite situated alongside the running water, but then the trail climbed a little hill, then dove down into a low spot again. As she crested the hill, she saw a gentlemen trying out his cell phone.

“Any reception?” she asked. He put his fingers up in a pincer shape.

“A little.” Cell reception was bad for most of the MRT.

As she hesitated, she turned and noticed the little narrow hill high off the trail to her left. It was high ground, flatish, possibly a good spot to sleep for the night. She climbed the spot and noticed it was empty, except for what looked like an ammo box in the low crotch of a tree. She walked back out to the trail and asked if the man intended to camp up there.

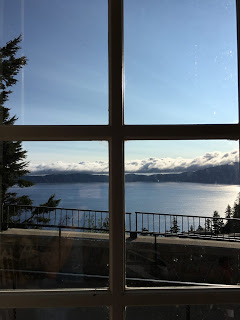

“No, no, I’m down there,” he said and pointed down over the bluff. Everyone seemed to want a water view.

She went back to the box and opened it, which confirmed her hunch. It contained bits and bobs and a log of visitors: it was a geocache. Nearby a fire ring of rocks indicated someone had thought it a good place to camp in the past, so she gladly took off her pack and walked, now light and free, looking for a flat spot, with no dead tree limbs hanging above, to put her tent.

After relocating her tent three times, she finally pegged it down, unpacked, forced herself to eat a scant dinner (she wasn’t really hungry), with some ibuprofen and acetaminophen for her aching hips and feet. Then she put her food bag up in a tree.

Bear bags were recommended, but the area rarely had bear visitors. The recommendation was probably to keep all wild animals with sharp pointy teeth away from campers’ tents.

Closed up in her tent, she got ready for bed, but then it was only 6:30 p.m. Because she packed for a later, colder weekend, half the stuff in her pack was unneeded, but not regrettably. Being prepared for differing circumstances statistically meant you would always carry more than you used, especially if things went well. She was willing to carry the insurance, and it was practice for carrying heavier packs for longer trips.

|

| MRT |

One thing she was thankful she packed was her e-reader. Books, to her, were always preferable to e-readers but the portability and capacity of the e-reader won out on hiking and camping trips. So she opened her device to Essays on Travel by Robert Louis Stevenson.

How apt, she thought. She had read his Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes where he documented a “backpacking” journey with a donkey to carry his things in the Cevenne Mountains. The narrative pulled and coaxed Astrid into documenting her travels, planting the seed that bloomed into the tiny, but significant step into backpacking.

Stevenson was plagued with poor health and attacks which left him bedridden for periods throughout his life, frustrating his ability to travel, except to various therapeutic climates, in hopes of healing his lungs.

Finally the clock at the top of her reader read 8:00 p.m., an acceptable time to go to sleep, so in the not-so-lonely dark, with voices of her neighbors down on the stream’s flood plain, the constant rippling watery gurgle of The Falls, and the constant rush of the Manistee River, a stone’s throw away, she fell asleep.

Around 3 a.m., wide awake and alert, Astrid wandered out to find Mother Nature’s WC, then read more of RLS’s dismal but creative life, before falling asleep again.

It was 8:35 a.m. when she next saw the clock. Dim light was filtering through the trees, calling all the hikers to pack up and hit the trail.

|

| MRT |

Astrid struggled and wrestled with dressing in the tiny, one-man tent, but eventually sorted herself out, broke down the tent, repacked her backpack, retrieved the food bag from the tree and dragged her tent tarp to sit on the ridge overlooking the vociferous stream and ate some cheese, bologna and nuts while she heated water for instant coffee on her backpacking stove.

The minute she put on her pack, she gasped in pain. It felt as if someone had put a rock in her shoulder strap. In reality, a slide from her undergarments had been positioned at a boney point in her shoulder that was very sensitive. Astrid steeled herself against the pain, put her pack back on again, but let most of the weight settle onto her sore (but not painful) hips and was on the trail again.

She saw a few hikers she passed the day before on the NCT. The lone hiker with the dog, the older lady, the couple, a mother-son pair. The mother stopped Astrid to look over her external-frame backpack, since she used an old one herself.

One exquisite encounter occurred at a high bluff over the river, a spot flanked with golden leaved trees and a meadow-like area beside her. Three young men were hiking toward her: the middle one with a puff of smoke trailing him. Astrid moved off the trail to let them pass.

Her first impression was negative, not wanting a whiff of cinder-cigarettes or unnatural smells of a vaping pen. But as the group moved closer, she smiled.

“Oh, it’s a pipe!” she said out loud and moved a step closer as the pipe smoker passed. “It smells so good!”

|

| MRT |

The smoker laughed and moved on, too quickly for her reminiscences. In her opinion, pipe smoke was the best aroma because at one time in her childhood, her father partook in the dying habit.

She passed the five mile mark, now aware that she had to relish every mile, it was the end.

To walk, and to do nothing else is, in a way, relaxation, rest, vacation. One may have loads of work to do somewhere; dishes in the sink, laundry piled high, in-boxes bursting at the digital seams, but when you walk out into the wilderness with all you need on your back, there is no room for guilt or work, walking will take you away, but it is also the only thing that will bring you back to your responsibilities and you can’t do much concurrent except look around.

As she walked along the path, back to Red River Bridge, she was tired in body, but rested in soul. The MRT side of the loop trail was, at every turn, magnificent. The NCT was a pleasant walk up and down wooded hills, but it was the more visually tame trail. The MRT lead along beautiful tree-backed meadows, along ravines with streams snaking the bottoms, treacherously close to the edge of a high bluff overlooking the elegant curves of the blue Manistee River.

Ready for responsibilities, but not wanting to go back, triumphant knowing she could walk ~14 miles, then 8 miles with 35 pounds on her back, but unsure if she could do more, as her hips and feet complained, she hobbled to her truck, and said goodbye to the beautiful Manistee River Trail Loop … for now.

Summary:

NCT :Trees and hills, bikers, no water for ~8 mile stretch, until you get to Eddington Creek. There are designated camping spots, but fewer than MRT, and farther between.

MRT: A lot of hikers, campers, day-hikers everywhere; more dynamic views.

If the Manistee River Trail Loop is a “D” shape, the NCT is the backbone of the D, the MRT is the curved, longer part, with the river dissecting the middle.

|

| No horses, but you can have llamas on the trail (bottom). |