|

| Manabezho Falls |

Like so many of Astrid’s adventures, it started with a book. Except this time, it was not a book she was reading, but a book she was writing. Enchanted with folklore from eastern European countries, she had used elements from Slavic fables in her story but needed some other element, a random detail that would generate material for her fictional world, something to fill details.

She settled on copper. It was the color of her hair, an unique and interesting metal and it would serve her purposes well. One of the main character’s ancestors, though not copper-topped, would make their fortune in copper mining in the industrial revolution. But where did copper come from? How was it mined? {This is how so many stories start … with questions, because what is a story, but an answer to a question or series of questions?}

Little did she know, she was already there. It used to come from Michigan (some of it). But more specifically, it came from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and even more specifically, from the Keweenaw Peninsula.

Little did she know, she was already there. It used to come from Michigan (some of it). But more specifically, it came from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and even more specifically, from the Keweenaw Peninsula.

The Keweenaw Peninsula is the north west part of the Upper Peninsula (UP) of Michigan, jutting into the wicked, wild Lake Superior. The UP is a piece of land which was granted to Michigan as a consolation prize in the Toledo War, when in 1835 Ohio and Michigan came to fisticuffs over a strip of land near Toledo. Ohio kept Toledo and Michigan was given the Upper Peninsula (which kinda looks like it should belong to Wisconsin, sorry Wisconsin). In order to lend some authenticity to her story, Astrid needed to know more about it, which lead her to the book, Boom Copper by Angus Murdoch. Besides the constant misogynistic comments (he likens Lake Superior, the earth, nature in general and anything the least bit of petulant to fickle womanish-ness), the book is full of prospector anecdotes and possible tall-tales about the history of the wild, wild, west that was the Keweenaw from the 1840s to the early 1900s.

Murdoch was a travel writer and, like Astrid, fell in love with the Keweenaw. He wrote of the history, from Douglass Houghton exploring the area, to the succession from the Indians, to the rumor of copper fortunes to the many prospectors that followed rumors of mineral riches in the ground. In reality, there were not as many fortunes made in The Copper Country, and in the gold rush in California as was thought, but a few notable men made off with riches.

Murdoch was a travel writer and, like Astrid, fell in love with the Keweenaw. He wrote of the history, from Douglass Houghton exploring the area, to the succession from the Indians, to the rumor of copper fortunes to the many prospectors that followed rumors of mineral riches in the ground. In reality, there were not as many fortunes made in The Copper Country, and in the gold rush in California as was thought, but a few notable men made off with riches.

In order to portray the area accurately in the story she was crafting, she scoured Google Earth online, looking at the land, noting the waterways, the tiny towns, the highways, the ports, even scrutinizing topographical maps to surmise the lay of the land.

Two more novels, ten years, and an education in camping later, Astrid made up her mind: she was going to The UP to see first hand where the character in her novels made his fortune. She wanted to see the rocks, breathe the frigid, damp air of the mines, feel the dirt, see the Lake, walk in the mines, touch the famous copper nuggets. This time, all the travel planning was up to her. Although they had taken a few trips to the eastern side of the UP (Pictured Rocks, Munising) as a family, Bjorn didn’t want to spend his precious vacation days on this excursion; he wasn’t interested in defunct copper mines.

On a Monday in August, after six months of planning, Astrid and Snorri packed the truck with tents, luggage and a sleeping-bag-wrapped cooler full of food and started on their journey to the UP. Why not hotels and restaurants? Because she wanted to be close to the outside, and save money.

The journey started in driving south, because sometimes the quickest way to Michigan’s UP from lower Michigan is through Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin.

She knew they were getting closer when the cities grew fewer and farther between, and the trees and forests grew thicker and closer to the road, with verdant green obscuring most of the field of vision. A sign advertising “Deer Heads Boiled,” was a definite marker telling they were in the wilds.

Their first stop was at Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, located south of Ontonagon, along the Lake Superior lakeshore. Astrid chose the first two nights accommodations at Presque Isle Campground, the “primitive” campground (no showers or electric or cell phone coverage). It was situated on a grassy bluff overlooking Lake Superior, sparsely peppered with vehicles and tents, but no large RVs.

Their first stop was at Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, located south of Ontonagon, along the Lake Superior lakeshore. Astrid chose the first two nights accommodations at Presque Isle Campground, the “primitive” campground (no showers or electric or cell phone coverage). It was situated on a grassy bluff overlooking Lake Superior, sparsely peppered with vehicles and tents, but no large RVs.

After setting up the tents, they walked to the far side of the camp, a little ways into the woods to a well with a squeaky hand pump for cooking and washing water, then lugged the big blue water jug through camp, nodding greetings to lounging campers.

They took a short walk to the Manabezho Falls, one of three shallow falls in the Presque Isle River which flows out to Lake Superior near the campground. They cooked dinner over their Biolite wood-fuel camping stove and a supplemental backpacking stove.

After dinner and cleanup, Astrid and Snorri walked down a long flight of steps to the “beach.” The beaches near their home in the LP (Lower Peninsula) were beige-sand beaches, with sandy bluffs, beach grass and some very interesting and sometimes copious stones. In the UP, there were boulders, bedrock, rock, rock, rock, mountains of rock. Campers swarmed the rock slabs of the shore, dipping their toes, splashing and watching the crimson sun sink into the lake.

After dinner and cleanup, Astrid and Snorri walked down a long flight of steps to the “beach.” The beaches near their home in the LP (Lower Peninsula) were beige-sand beaches, with sandy bluffs, beach grass and some very interesting and sometimes copious stones. In the UP, there were boulders, bedrock, rock, rock, rock, mountains of rock. Campers swarmed the rock slabs of the shore, dipping their toes, splashing and watching the crimson sun sink into the lake.

Back at camp, by the light of a citronella candle (the flies weren’t really bad), Astrid looked over the map of the Porcupine Mountain Wilderness State Park hiking trails and picked a few options.

Early the next morning, after breakfast of sausage and eggs, and coffee and tea for Astrid, they threw their packs in the truck and drove on South Boundary Road to the trailhead of Summit Peak Summit Area, walking half a mile to Summit Peak Overlook. Out over the platforms was an ocean of churning green.

Astrid was born and raised in Northcentral Pennsylvania, in a valley skirted with low, rolling mountains covered with deciduous trees and patches of rocks. It was what she saw when she looked out any window, took a walk, rode in a car, in every direction, constantly until she moved out of the state. The mountains she saw at the Summit Peak Overlook were very similar to the mountains of her hometown PA. They weren’t impressive like the naked towering Colorado Rockies, or the icy black mountains in Iceland or the bright green cliff-filled hills of Scotland. They were familiar to her as if she were seeing the back of her hand on some other person. Except in PA, there was no Great Lake glimmering in the distance.

To Astrid, “outside,” when conditions were tolerable (or, at most, challenging), was always preferable to “inside.” Rural “outside” was more favored and enjoyable than urban “outside.” Forested “outside” was downright magical. It was the trees, she thought: the perpendicular monuments to biochemistry, the totems of biomass accumulated through iterated years of rain, sun, warmth, growth, cold, dormancy, then budding out. They filled the forests with seemingly random but infinitely ornate architecture, and as she walked among the silvan landscape, it always quenched some unutterable thirst.

After the short hike to the overlook, they trotted back down to the parking lot then started on the South Mirror Lake Trail. The first part of the trail lead them through a heavily forested area, along a stream, then over a bridge that spanned a wild-flower adorned swamp, then back into thick woods again. They walked past backpacking camping sites with bear poles, over marshy areas on raised platforms.

Once at Mirror Lake, they sat on a log by a dead fire pit and ate the lunch they had packed that morning. A hiker with a gigantic, furry black New Foundland, what he called “just a puppy,” walked by and let them pet the magnificently soft giant dog.

|

| Mirror Lake |

On their hike back, Snorri regularly switched his backpack to his chest, as it was agitating him in some way. When they reached the trailhead parking lot, it was full of cars, and the road in lined with vehicles.

Driving along South Boundary Road, the road that skirts Porcupine Mountain Wilderness State Park to the south, Astrid slowed at any sign of pull-offs and trailheads, taking note of possible activities for the next day, until they arrived at the visitor center and park headquarters. Here, Astrid used the Wi-Fi to communicate with folks back home, since there was no cell signal anywhere but the highest peaks in the park.

From South Boundary Road, they turned onto 107 Engineers Memorial Highway and drove west, up a steep hill to Lake of the Clouds Overlook. Astrid didn’t go up to the UP just for hiking, and being outdoors. She wanted to see fragments of history, so they parked at the trailhead for The Escarpment Trail, which intersected some old mines. Snorri was tired, and didn’t hide the fact.

“We’ll walk until we come across a mine,” Astrid said, encouraging the tired boy.

The first quarter mile of the trail was covered with large gravel (dug out of a mine) which made sense when less than a half mile up the mountain, way sooner than Astrid expected, a rotting sign stood warning of caution stood, announcing the Cuyahoga Mine. It was just a biggish hole in the ground, but to know some codgery old prospector sank all his heart and soul and future into this spot a century and a half ago was a thrill for Astrid to see.

Snorri gave a look, turned around, then started down the mountain.

“Where are you going?” Astrid asked.

“You said, when we reach a mine …”

She did say that, but wanted a longer hike.

“That’s way too short. I didn’t expect the mine to be right here … let’s go up to the top … or at least until we hit one mile,” she said, turning on the GPS tracker to count the distance.

Astrid walked up the mountain, marveling at the many birch trees, thick, white barked pillars along the trail. Some birch stood dead, the rotting insides of the trunks held together and up by the very sturdy and weather-proof papery bark. At the top was a rock outcropping that provided a cleared spot and a great view of the surrounding mountain tops. Snorri trudged up a few minutes after her.

“Now, can we go down?”

“Just a minute … look at the view … look at this rock here, see the vein of red … relax, we have time,” she said.

After a few minutes of taking in the prospect, she said, “okay, now,” and Snorri turned tail and rushed down the mountain, reaching the car a full ten minutes before her.

After a dinner cooked over the backpacking stove, Astrid went down to the rocky shore and waded in the chilled water, carefully, because the rocks were often covered with slimy moss.

That night, they fell asleep to the sounds of a newly arrived family reading a night time story at the next campsite.

The next day’s plan involved many stops, the first after breakfast being an impromptu hike at The Union Bay Interpretive Trail, an one mile trail loop around and across the former Union Mine sight. It followed a stream, of course, because most mines needed water. Deep, wide holes in the ground were fenced off, informative signs posted at many significant spots and trail markers on trees.

Next, the GPS lead them to the Adventure Mining Company, where they toured the dark, damp, copper-studded tunnels of the Adventure Mine in Greenland, MI. The mine, open between 1850 and 1920, took out eleven million pounds of native copper and was now used for tourism and, of all things, bike races. Yep, they rode bikes through the mine.

Next, the GPS lead them to the Adventure Mining Company, where they toured the dark, damp, copper-studded tunnels of the Adventure Mine in Greenland, MI. The mine, open between 1850 and 1920, took out eleven million pounds of native copper and was now used for tourism and, of all things, bike races. Yep, they rode bikes through the mine.

The tour guides first loaded the group up into old WWII people-moving vehicles, but not before providing hardhats, and boot disinfectants (to prevent a fungus called White Nose Syndrome which kills the mine bats). Walking over rough, gravel-lined tunnels, the guides explained the copper mining history, bats, and even the B- movie that was shot in the mine. The light-colored damp walls glistened with white calcium rock, some kind of fungus, moisture, and sometimes, copper.

In the gift shop, Astrid bought the book that started it all, Boom Copper, and Snorri chose an old mining drill bit as a memento.

Traveling further north, they stopped for lunch at Rockhouse Grill and Tavern in Houghton, MI, then restocked their cooler at a Walmart there. It was a typical Walmart with crabby customers and shopping carts jammed into Astrid\’s parked truck, but there was one other very useful thing she found.

“… and one block of ice,” she said when the cashier finished ringing up her staples.

“Are there some there? ‘Cause I wouldn’t want to charge you and there not be any. We run out,” he asked.

“Oh, yeah, I checked,” she said. For three days, frozen gallon jugs of water in her sleeping-bag-wrapped cooler kept all the perishables from perishing, and it was working well. The ice was still very much ice, but it was melting, and a block of ice, rather than a fast-melting bag of ice cubes would be just the thing to help get them through another three days of the mild summer heat.

They drove through Houghton proper, crossed the Portage Canal Lift Bridge into Hancock, past the magnificent Quincy Mine, one of the most successful mines in the UP, but they didn’t stop, then continued north on Route 41 with a rain storm on their trail. A few miles north of Hancock, Route 41 becomes wooded and lonely. The forests are whiter than the ones in the lower peninsula, populated with birches more abundant and larger than Astrid had ever seen.

They arrived at the nicely wooded Ft. Wilkins Campground West, along Lake Fanny Hooe, and hurriedly set up their tents to avoid the rain, then head to the shower house for long-awaited showers. By the time they were done, it was evening and getting dark because of storm clouds, so they turned in early. Astrid started on her book, Boom Copper, then fell asleep to the patter of rain on the tent.

|

| Lake Fanny Hooe |

The next morning after breakfast Astrid took a good long look at the weather forecast for the day and decided to take a walking tour of Ft. Wilkins first, and save the mine tour for when it rained later that day. Ft. Wilkins was built in 1844 as a military outpost to protect miners from Indigenous peoples and keep order, but it turned out largely to be unneeded. The buildings showcased soldiers’ quarters, kitchens, and various old outbuildings, including a blacksmith’s shop.

Next they stopped at Brockway Mountain Overlook, looked over Copper Harbor and the surrounding mountains, then programmed GPS to Delaware Mine.

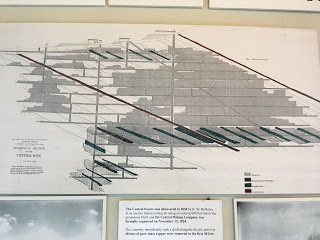

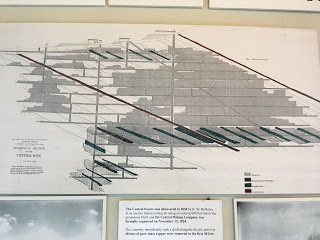

|

| The Central Mine, 14 levels down |

|

The Delaware Mine is now a tourist attraction, but in its day it employed hundreds of miners, primarily from Cornwall, England, and brought up eight million pounds of copper from 1847 -1887. After paying for admission in the gift shop, and petting the mine’s dog, the proprietor asked,

“Wanna see my pet?”

When someone is asked this question, it is best to take into consideration where one is. If someone asked Astrid this in the middle of a big, metropolitan city, she would probably say no and run. But she was in Michigan’s UP.

The proprietor took a small basket from behind his desk, set it down and pushed some of the straw aside to show a furry black thing with a dark nose nuzzling deeper, away from the light.

“A skunk?” Astrid asked. “Oh, so sweet! Snorri, come see!”

“He’s sleeping and won’t want to wake up, but you can look.”

Astrid gooed over the furry little animal a few minutes, not even bothering to ask if it was still “loaded.” After watching a short film on the history of the mine, they donned hardhats with lights and self-guided themselves down steps a few stories into the mine. This mine was full of reddish rock. Huge timber beams lay here and there, some blocking deserted shafts. As they walked the length of the shafts, little bats fluttered high above them in the cold, damp air. At the very end of the level there was a shaft heading down at a 45 degree angle into infinite darkness, and to know that there were half a dozen levels, albeit, now filled with water, below them, brought on a certain claustrophobia that made Astrid shiver.

Astrid gooed over the furry little animal a few minutes, not even bothering to ask if it was still “loaded.” After watching a short film on the history of the mine, they donned hardhats with lights and self-guided themselves down steps a few stories into the mine. This mine was full of reddish rock. Huge timber beams lay here and there, some blocking deserted shafts. As they walked the length of the shafts, little bats fluttered high above them in the cold, damp air. At the very end of the level there was a shaft heading down at a 45 degree angle into infinite darkness, and to know that there were half a dozen levels, albeit, now filled with water, below them, brought on a certain claustrophobia that made Astrid shiver.

After emerging from the mine where it was a cool 52 degrees into mid-80s, they walked around the grounds, reading about the remains of stamping mills, processing buildings and whatever was left of the mine operations. Astrid bought a nugget of native copper as a memento.

At the Jampot Bakery, run by monks, they picked up some monk jam for Olaf, and some chocolate bars, Astrid marveling at the shelves of jam and the beautiful Eastern Orthodox icons on the walls. Snorri wanted to stop at the Blacksmith exhibit, then they set the GPS for the Laurium Manor Hotel.

Astrid loved old houses: the smell of the old wood, the ornate architecture and the history infused into every nook and cranny lit up her mind with interest and imagination. The Laurium Manor Hotel was a working hotel, so they couldn’t go into the rooms that were occupied, but there was plenty of 19th Century opulence to see as they walked through the Manor-Hotel, marveling at the ornamental detail and craftsmanship and the old-time luxury copper fortunes had bought.

Astrid loved old houses: the smell of the old wood, the ornate architecture and the history infused into every nook and cranny lit up her mind with interest and imagination. The Laurium Manor Hotel was a working hotel, so they couldn’t go into the rooms that were occupied, but there was plenty of 19th Century opulence to see as they walked through the Manor-Hotel, marveling at the ornamental detail and craftsmanship and the old-time luxury copper fortunes had bought.

Eagle Harbor Lighthouse was very similar to the lighthouses they had toured in the lower peninsula, like Little Sable Point and Big Sable Point, etc. They were quaint houses attached to big cement towers topped with lights. After climbing to the top and back down, they explored the magnificent rock formations on the shore

Dinner was salmon fried over the camp stove at Ft. Wilkins Campground, then Astrid visited the historic fort again, taking in more detail and pictures.

In the UP, along the road she saw signs for thimble berry jam. At the monk’s bakery, she saw jars of it, expensive at 18$ a pint. But what was this thimble berry? A little chagrined to be a plant-person and not know what it was, she made a guess. Along the path to Ft. Wilkins was a plant she had seen before, in Michigan forests and in Pennsylvania, but didn’t have a name for it. It had lobed, hirsute leaves, spiny stems, raspberry pink or white flowers and very-raspberry looking fruit, except bigger and less copious. She guessed right: the berry that was all over the UP and sprinkled in the forests was Thimbleberry, or Rubus parviflorus.

|

| Thimbleberry |

The next morning after breakfast they packed up camp and drove Brockway Mountain Drive 26, lined with plenty of pull-offs and overlooks, before leaving the Keweenaw Peninsula. After passing back through Hancock, then Houghton, they drove by Michigan Technological University, where Highway 41 hugged Lake Portage, then made a bee-line for the shores of Lake Superior, as if the road longed to be near water. Around Baraga, MI is one of the most beautiful drives, with the highway just a few hundred yards from lake and the surrounding land lay flat, with a clear view across the L’Anse Bay.

They crossed the five-mile Mackinac Bridge into the LP, hung a right, drove a few miles and found their campsite at Wilderness State Park, which was a dark park. It was not as silvan or wild as Ft. Wilkins’ campground. Maybe it was because of the Perseid Meteor Showers that weekend that filled the park to capacity (a family looking for a last minute site at the registration desk was turned away). Looking down the crowded paths, one only saw trailers, RVs, huge tents, campers, cars and trucks.

|

| Pancake, in pie iron, over a camping stove. |

Astrid and Snorri’s campsite for the night was wedged between a huge camper and a mid-sized RV, both with all the trimmings: canopies, fire-ring, a dozen lawn chairs, strings of gaudy lights, and tents for overflow sleeping. But though the interior of the camp was packed to the gills, on the other side of the tree line at the back of their site was a section of the beach to Lake Michigan, much calmer and clearer of human traces than the front. Astrid set up her tent, Snorri his hammock (because they would only be there for one night), cooked dinner then took showers. After some reading on the beach and exploring the area, they went to bed and fell asleep to the fire-side conversations of their neighbors.

|

| The back of the campsite |

Before setting off the next morning, they stopped in Mackinaw City and picked up some Mackinaw fudge after looking through the many tourist shops there. The whole family had been there years before, took the ferry to Mackinac Island State Park and did everything that a trip to the island entailed. Astrid often referred to it as the “Gatlinburg (Tennessee) of the North,” having similar touristy auras.

The five-ish hour drive back to Southwest Michigan seemed like ten because Astrid was tired, but she didn’t want to stop except for gas. By the time they drove through the cherry growing region of Michigan, then through the peach-growing region, back to the grape-growing region of the sandy shores of lower Lake Michigan, they were tired. There was still ice in the cooler. As Astrid unpacked the tents and everything that went with them, she was happy, fulfilled.

Ten years before, she had questions, “What did the first copper prospectors experience up there? What does the UP of Michigan look like? What was is it like at the tippy top of Michigan?”

And now she had some answers: As to what the prospectors experienced, she knew she saw only the good side of the weather: mild and kind with just a few showers to make things interesting. Winter was often long and cruel up there. As to what the UP looked like? It is an extraordinarily beautiful wilderness with raw rocks, wonderful parks and exquisite wildernesses.

|

| Fort Wilkins |

Not much grew under the trees, they were too tall and too massive to allow a lot of light to fall to the forest floor. The massive trees caught all the sun in their leafy fingers before it fell to the ground. There were patches of ferns and sorrel in the spots blessed by beams of sun that snuck through the branches. Moss grew on the lesser trees.

Not much grew under the trees, they were too tall and too massive to allow a lot of light to fall to the forest floor. The massive trees caught all the sun in their leafy fingers before it fell to the ground. There were patches of ferns and sorrel in the spots blessed by beams of sun that snuck through the branches. Moss grew on the lesser trees.  There is something about photographic technology that does not record the nuances that humans use to perceive each other, themselves, and their world. Maybe it involved other senses than seeing, maybe the fault was in the camera, maybe it was something else.

There is something about photographic technology that does not record the nuances that humans use to perceive each other, themselves, and their world. Maybe it involved other senses than seeing, maybe the fault was in the camera, maybe it was something else. “Good morning,” a passerby whispered–and aptly. Whispers seemed most appropriate, as if the park were some very hallowed place. It was something about the trees–their majesty, power, age, achievements–which called for respect and reverence. The trees seemed to absorb the noise, shushing visitors to contemplation and peace.

“Good morning,” a passerby whispered–and aptly. Whispers seemed most appropriate, as if the park were some very hallowed place. It was something about the trees–their majesty, power, age, achievements–which called for respect and reverence. The trees seemed to absorb the noise, shushing visitors to contemplation and peace. To leave the park was a small heartache to Astrid, but they couldn’t stay forever, and she knew that even if she lived among them, she could never understand the spell they had over her. Better to preserve the mystery and awe, than overstay her welcome.

To leave the park was a small heartache to Astrid, but they couldn’t stay forever, and she knew that even if she lived among them, she could never understand the spell they had over her. Better to preserve the mystery and awe, than overstay her welcome.